Interviews Toshiko Mori: Teaching and Practice

Adapted from Toshiko Mori’s 2019 AIA/ACSA Topaz Medallion Acceptance Speech

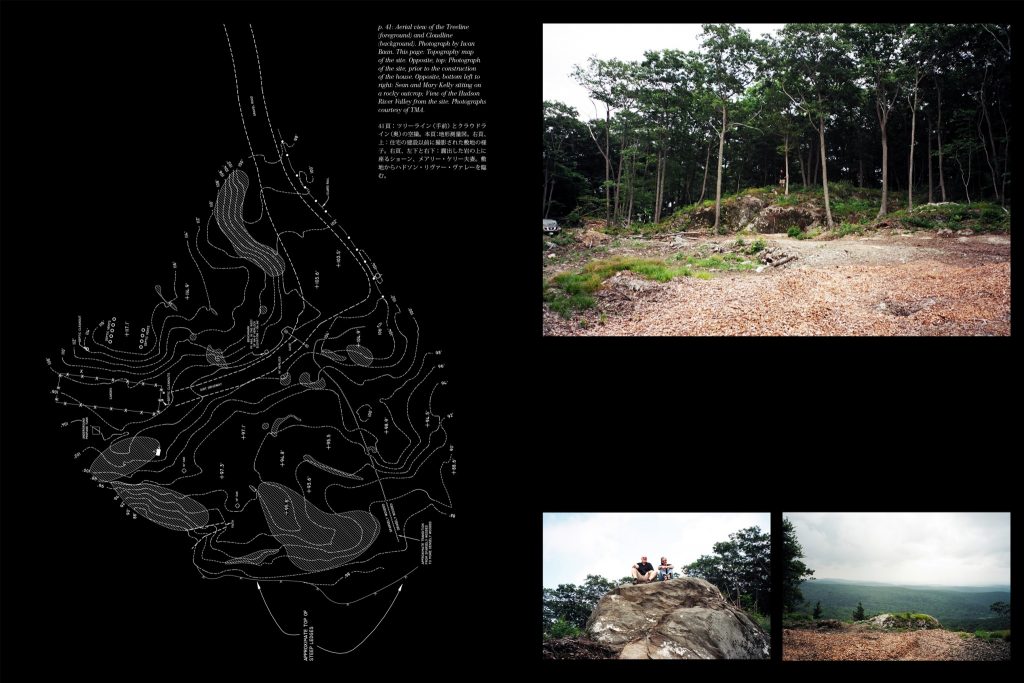

My work as an architect has always been situated between multiple contexts, material and otherwise. At once enfolded into the picturesque landscapes of the Hudson Valley or the historical legacies of coastal Maine, the plans on the table at Toshiko Mori Architect derive their vitality from the sites and contexts in which they eventually rest. From another angle, my practice also draws from the wellspring of an academic milieu, animated and assisted by students, colleagues, and institutions, both former and current. Within and between this contextual dialogue, my practice finds its footing. The projects presented here discover their meaning by leveraging connections with the site, with history, and with each other; their presence expands by engaging theories of architecture, art, culture, and science: the material and immaterial. This work is a product of that contextual dialogue, weaving between and across influences, legacies, and settings.

The simultaneity of context means that inspiration neither begins nor ends in one site or another. My work has sought to amplify an expanding field of contextual relationships by including those materials, strategies and perspectives which have been siphoned out of architectural discipline proper and set up as niche practices of their own. We have dedicated our work to the study of materials, ecological impacts, and the integration of academic experimentation, all which address the social and cultural paradigms that affect our daily lives. These interests and their interplay have flourished throughout almost forty years of architectural education and have benefitted, first and foremost, from the continuous, vibrant exchange with mentors, students, and colleagues along the way.

Learning

I was lucky to have incredible mentors such as Edward Larrabee Barnes, Isamu Noguchi, and Kazuo Shinohara who gave me opportunities to work with them or offered me valuable life advice as personal friends. They were, and continue to be, my teachers. Following their example, in my life as a practicing architect, I have always taught, and have been taught in return.

I first began teaching at Cooper Union when John Hejduk served as dean. His influence guided me through my first experiences as a teacher at the start of my career. Hejduk, another significant mentor in my life, always said that “teaching is the birth right of architects, do not give it up!” With this quote, he expressed multiple meanings. First, our society gifts architects the opportunity to build and in return, we must offer the knowledge we gain through the social and tectonic act of building to the next generation. Secondly, our work as architects will always involve teaching as a form of constantly elucidating the substance of society in general, inside and outside of the walls of the academy. I was influenced by his education-as-social-contract philosophy, his pedagogy based on tectonics, and his poetic and philosophical outlook on architecture in cultural contexts and societies. His rigor for precision in achieving clarity of ideas and encouragement for creative productivity resulted in projects which reflect each student’s personality. Authenticity of work is what he prized most; he discouraged and despised imitation of others’ work and especially that of teachers. These are the thoughts and focus I have kept throughout four decades of teaching.

He also said: “Students keep us honest.” For Hejduk, teaching was always a two-way street where teachers could learn as much from the students as they could from us. With fresh and genuine interest enmeshed with excitement for the study of architecture, students indeed kept me challenged and honest all my life. My role as their teacher does not end with their graduation. In fact, I believe teaching is the continuous work of architects always in parallel to practice.

Since my firm, Toshiko Mori Architect (TMA), was founded in 1981 it has grown alongside my role as an educator. In my opinion, teaching and the practice of architecture are intrinsically intertwined. I do not know many other professions or disciplines where so many members are involved in education in one form or another. Both my practice and approach to education is grounded in a respect for the individual and the humanistic, as well as a desire to expand and explore the role of the architect in society and the world. As architects, we teach society at large by enlightening it with our work as much as we formally teach students within the school’s walls. Throughout my career, I have worked on a broad range of programs and scales, including the renovation, restoration, and addition of buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, Marcel Breuer and Paul Rudolph. My studios and my approach to teaching – with a sensitivity to historical precedents, community contexts, and sustainability – reflect my experience with these challenges in my own work.

Teaching

At the start of my career, architectural academia had just begun to change toward an embrace of diversity in scholarship and in voices. I was invited to teach at Columbia University and Yale University where I was the Eero Saarinen Visiting Professor in 1992. After teaching at Cooper Union, I joined the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) in 1995 under a new pedagogical model. My title, Professor in the Practice of Architecture, was the first appointment of its kind in which the university formally recognized the value practicing architects might add to the students’ professional education. Though I was not aware at the time, in 1995 I became the first woman faculty member at the GSD to earn tenure. From 2002 to 2008 I was also the first woman to chair the Department of Architecture. In my twenty- four years at Harvard, I have had the pleasure of teaching and advising generations of young architects. Many of my students went on to distinguished careers of their own.

One of my focuses as chair was to grow the department by fostering new and upcoming talents. Rather than catering to already-established names, I saw an opportunity for students to learn by osmosis, influenced by the tremendous energy, focus and drive of new voices and talents. As an administrator, I felt it necessary for an institution to positively support the careers of junior faculty and to give them opportunities to showcase their work on a public platform. By offering responsibilities to organize conferences, curate exhibitions, and edit publications, I hoped to prepare them to become future leaders of architecture and its education, while simultaneously preparing students for the same journey. We worked with our students to broaden the base of craft and materiality and to explore the larger contexts of architecture in contemporary society. I have introduced a stronger focus on material studies, addressing a weakness in the GSD’s curriculum – at that time also a weakness in architectural education throughout the US. The new focus on materials would come to include the addition of a required material course and workshop to the first-year core sequence and new seminars exploring traditional materials, new materials, a fusion of the two, and innovation in fabrication. Several option studios I’ve offered since have engaged these issues in a studio format, allowing students the flexibility of personal experimentation within an expanding horizon of tools and issues. Studios focused on the preservation of modernism icons, local histories, and contextual scarcity, in sites from Finland to Japan to Senegal, and have challenged students to confront the non-hypothetical. Students were necessarily engaged with imminent, real issues and stakes for the local communities, resulting in a studio environment enriched with a sense of purpose and idealism.

Under these new initiatives, I made it a priority to pursue a stronger engagement with ecology, sustainability, energy efficiency, paired with innovative structures, engineering, and technology in order to expand the conversation on material studies. Focus was also redirected toward navigating digital technology beyond simply visual expression, concurrently investigating, and investing in, fabrication and simulation tools. We developed a series of seminars titled Global Redesign Projects positioned to address large, unwieldy topics such as climate change, population explosion, urbanization and food and water scarcity through the lens of architecture’s many capabilities, including visualization and material innovation. These courses are part of a larger commitment to strengthening the dialogues, connections, and roles for architects in the world.

That said, the materials architects need to embrace are beyond steel, concrete, brick and glass. They include that myriad of subject matters which run through and effect our complex world. If one examines it, architects already embrace these expanded topics in their discourse. And, what’s more, in global discourse the word “architecture” is used often in the political realm to describe the presence of a credible organization and structure. This idiom might seem a result of wishful thinking, nevertheless we as architects need to expand our capacity of organization and the ability to understand and assimilate complex subject matters into more public discourse. In large multifaceted relationships, the most fragile areas exist between isolated expertise silos and disciplinary blind spots. Our ability to cut through subject matter to find connectivity, as a function of architectural thinking is a significant analytical tool to diagnose and isolate hidden or previously unexamined entanglements in political, social, and cultural arenas. Finding multidisciplinary fragility in between top-down and bottom-up socio-cultural structures – such as disaster remediation efforts or in between threads of knowledge which relate fresh water use and renewable sources of ocean energy – allows people to identify and relate systems of cause and effect. This type of investigatory weaving provides suggestions for solutions, crossing over datasets and typological models to arrive at intersections of information which may give a new combinatorial insight into future possibilities.

Toshiko Mori, FAIA is the founding principal of Toshiko Mori Architect (TMA) PLLC, and the Robert P. Hubbard Professor in Practice of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD), where she served as chair of the Department of Architecture from 2002-2008. She is a graduate of the Cooper Union Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture and holds an honorary master’s degree from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Learn more here.