Interviews Wilfried Wang on Heinz Bienefeld

Introduction: Heinz Bienefeld – Drawing Collection

Wilfried Wang

Four decades ago, a+u (No. 154, July 1983) was the first international architectural journal to publish a collection of buildings by the German architect Heinz Bienefeld (1926–1995). At that time, his very small body of work was known only to Germans, and principally those living in the archdiocese of Cologne. Bienefeld had two groups of clients: the church and couples. Towards the end of his life, the church officials’ impatience with him grew due to his meticulous and slow way of working, while his private clients exchanged their experiences with “their architect” in psychological preparation for the test of endurance that the typical four years of design and construction of a house by Heinz Bienefeld would require of them.

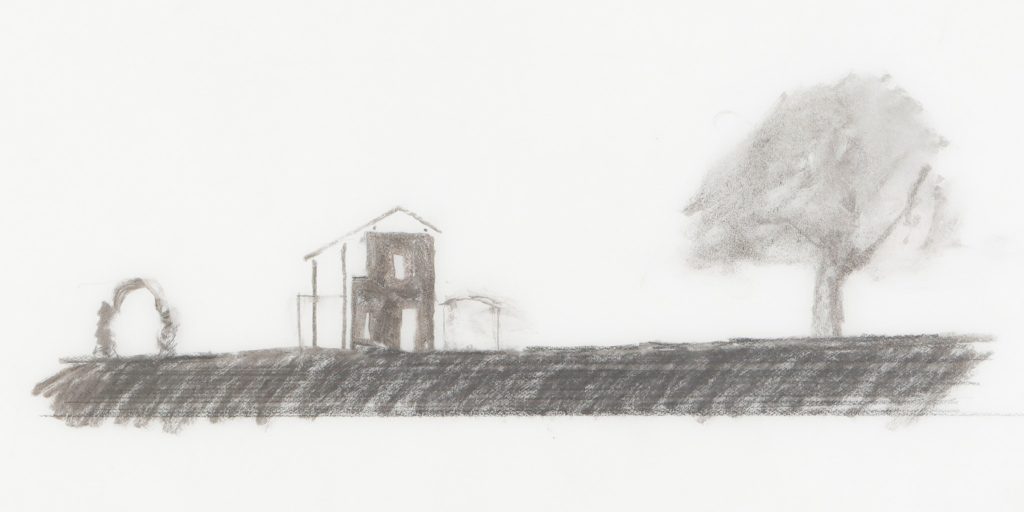

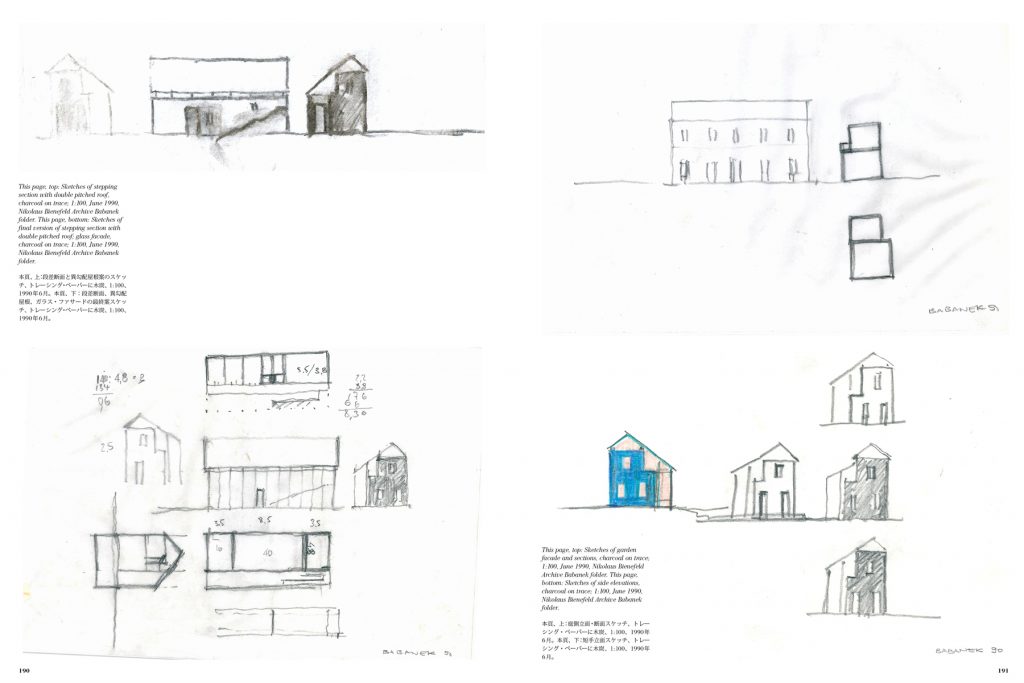

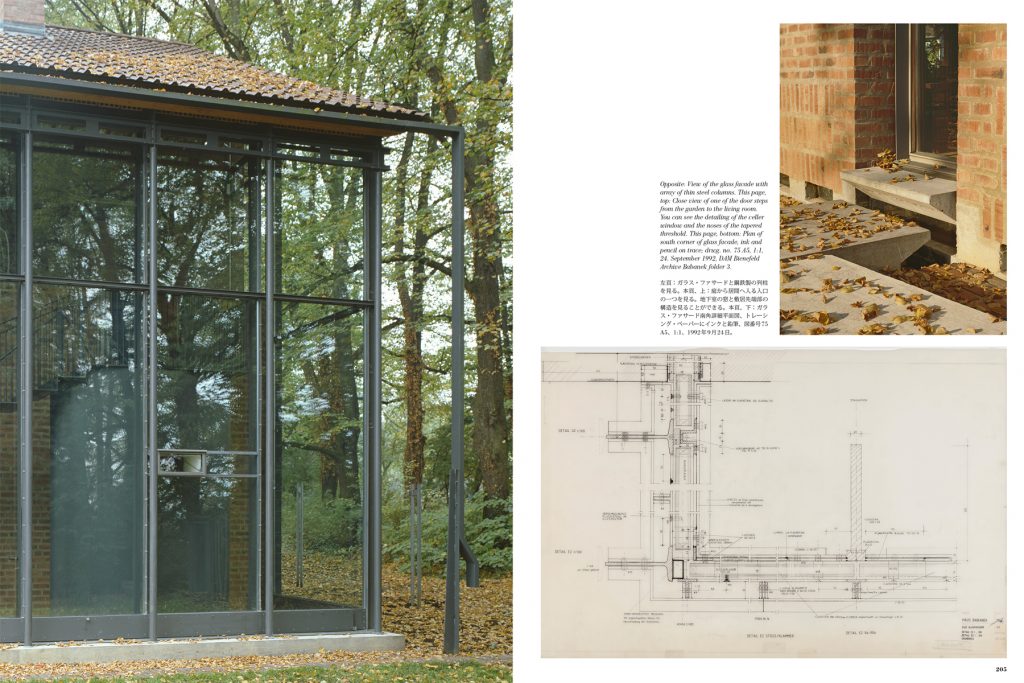

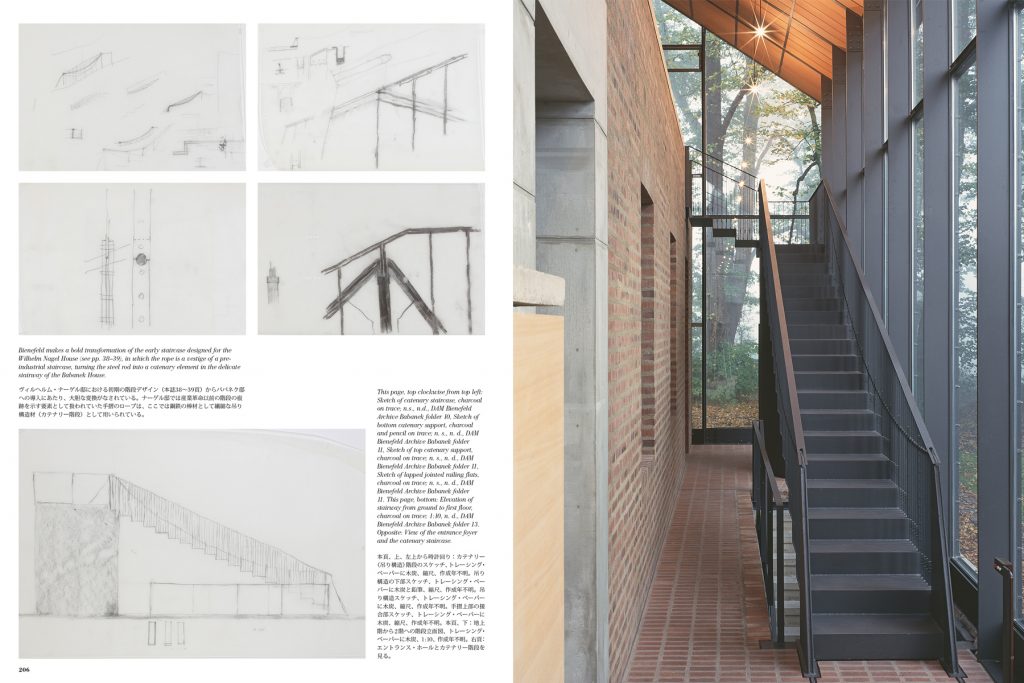

Seen from the vantage point of the 21st century, the intensity and time that Heinz Bienefeld devoted to each building, each floor, each wall, each roof, each door and each window would appear to most architects to be at best sheer madness, and at worst utter commercial and professional suicide. This special issue of a+u provides an in-depth insight into the working method of Heinz Bienefeld. Five representative buildings have been selected from his 180 projects: two churches and three houses. They span his career and they mark his way of thinking beginning with the search for the right typology, often starting from the simplest and most orthodox solution, then transforming this type under the detailed study of the different elements, and ending in the constructional details. Heinz Bienefeld would work systematically from the seemingly naïve small diagram of a building, often producing stamp-sized ideograms that like a microchip, already held much information, then increasing the scale of the drawings from 1:100 to 1:50, 1:20, 1:10 and ultimately to full scale. The scale of 1:10 was the one Heinz Bienefeld cherished. Here surfaces, profiles and assembly process could be tested in his mind’s eye. For each of his buildings, there are hundreds, sometimes thousands of sketches and drawings, some quickly produced, others clearly the result of many hours of drafting, correcting and re-drafting.

At the time of Heinz Bienefeld’s death, digital technology was making inroads into the architectural profession. Today, there are hardly any young architects who draw any sketches of anything in any medium, let alone sketches of construction details in charcoal, Bienefeld’s favourite medium. With BIM and the many corporate component producers, most details that are built these days follow a standard set by the respective industry lobby groups. Heinz Bienefeld designed individual windows and doors, even door handles, few of which would meet contemporary building codes. So why should we pay any attention to the work of an architect who built little, albeit with great intensity and invention, when what he built is unlikely ever to be available as a ready-made library component in the latest BIM software? What can one take from the work of Heinz Bienefeld? The shapes, the patterns, the typologies? Or might it not be more than that?

The format of this special issue is such that the concentration on just five buildings by Heinz Bienefeld should serve to communicate to the interested individual the core of his thinking and design. This special issue begins with the early house for Wilhelm Nagel, an evocation of the compact spatial and proportional relations of Andrea Palladio. This is followed by two churches, St. Willibrord and St. Bonfatius, the first an introverted polygonal enclosure that is treated like a public square and the second an octagonal capsule protected by a generous roof on six pillars. The Heinze-Manke House from the intermediate and the Babanek House from the late period complete the presentation.

Heinz Bienefeld’s work is noteworthy even or especially for our times, as his search for the substantively essential did not end with superficially minimalist shapes, but with spaces and details that speak of their long cultural history in a contemporary abstracted version.

Wilfried Wang is the founder of Hoidn Wang Partner in Berlin, with Barbara Hoidn. Since 2002, he’s been the O’Neil Ford Centennial Professor in Architecture at the University of Texas, Austin. He was born in Hamburg, studied architecture in London, and was a partner, with John Southall, at SW Architects. He was founding co-editor, with Nadir Tharani, of 9H Magazine and co-director, with Ricky Burdett, of the 9H Gallery. He was the director of the German Architecture Museum, curator of a retrospective exhibition on the work of Heinz Bienefeld in 1999, and co-editor of the catalogue, Die Architektur von Heinz Bienefeld (Frankfurt am Main, 1999). He has taught at the Polytechnic of North London; University College, London; Harvard University; ETH Zürich; and Universidad de Navarra. He is an author, editor, and curator of various architectural monographs and exhibitions, and editor of the O’Neil Ford Mono- and Duograph series. He is also chairman of the Erich Schelling Architecture Foundation; foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm; member of CICA; member of the Akademie der Künste, Berlin; honorary member of the Portuguese Chamber of Architects; and has received an honorary doctorate from the Royal Technical University Stockholm.