Friday The Shinkenchiku Library

The Shinkenchiku Library is a weekly series on au-magazine that introduces out-of-print publications from the 96-year-old Shinkenchiku-Sha archive. This is the 3rd of 4 parts to Chapter 1 of the book, Architecture of the Shōwa Era (by Hiroshi Sasaki, 1977) – The Status Between 1925 to 1930.

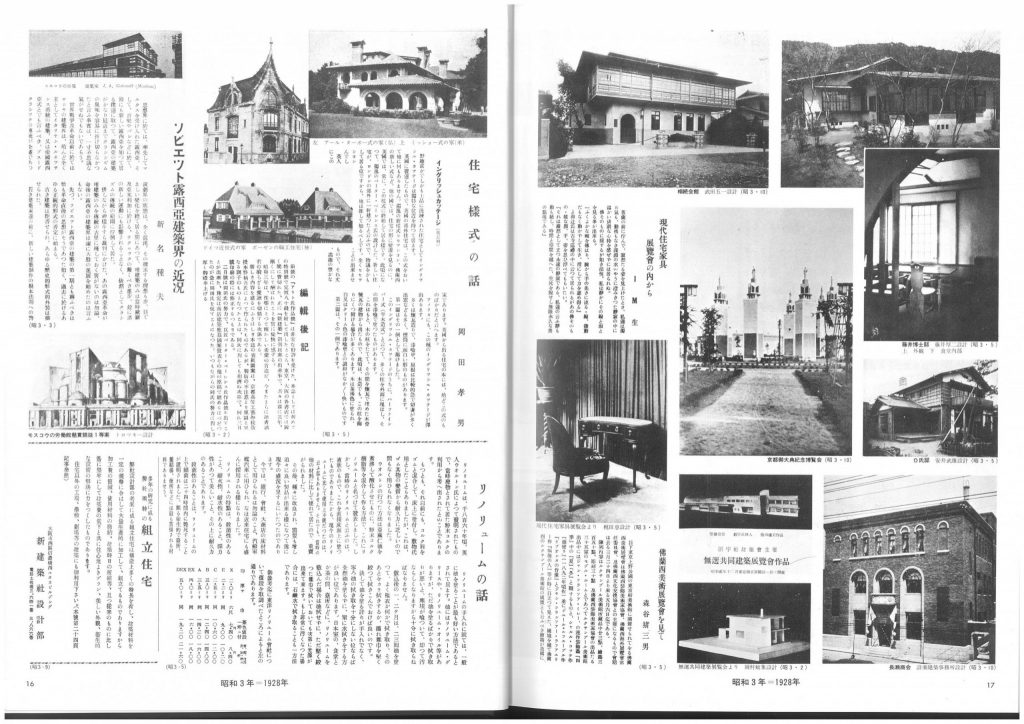

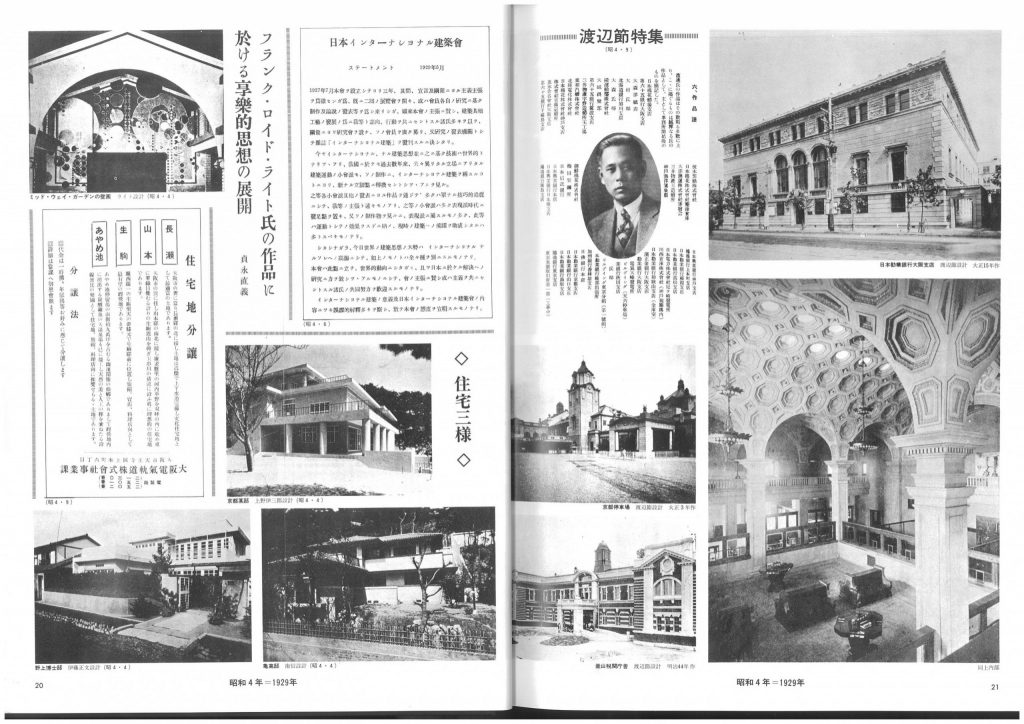

For what it was first recognized as an architecture magazine intended generally for enthusiasts, Shinkenchiku began to carry more architecturally specialized articles. Additionally, the magazine dealt with themes such as new foreign architecture, ancient Japanese architecture, earthquake reports, and even facades. The intention was not only to showcase architectural design but also to explore the history and modern environmental studies.

In these early days, the process of trial and error continued vigorously when architectural media was not yet established. Over time, the process was formalized.

Below is an excerpt from the text.

___

“With these special features, the readers’ intellectual curiosity was greatly stimulated, and the response was heightened. Eventually, Shinkenchiku was regarded as a proper architectural magazine. Accordingly, the number of circulation also increased.

At the same time, the “personality” of the publication since its first issue was gradually changing. While the number of new city features (initially intended) for enthusiasts decreased, the number of articles dedicated to the architecture and construction industry increased. This revised “personality” is a closer reference to today’s architectural magazines. However, it can be said that the original perspective of including architecture as a comprehensive form, was lost.

Looking back at the table of contents of the first issue and subsequent issues, one could see that Shinkenchiku gradually moved on to cover a wide variety of topics, including new foreign architecture, classical foreign architecture, new Japanese houses, old Japanese architecture, building structures, building materials, earthquake reports, facades, various housing facilities, gardens, design consultations, and many others.

Although these topics featured might have been considered to be diverse, the consensus was that the magazine introduced a range of “miscellaneous” topics.

However, the editorial policy is such that it is not merely about showcasing how architecture was designed. It can then be inferred that there was an intention to grasp and convey various ideas and issues from various aspects (in the architecture field).”

“It took a few years to iron out some confusion. Takao Okada (1898-1993), who was then deeply involved in editing, – one might think he was a full-time employee – tried to reflect on the overall character of architecture from a particular aspect through the book called “Architectural Works” 「建築家の作品集」.

Additionally, as Shinkenchiku is a magazine born in Japan during the transitional period of architectural design, by introducing architects and architecture, not only was the character of the magazine determined. The orientation of Japanese architectural design was also defined. Naturally, it was the ambition of the publication to fulfill these points.

Following the undertaking of Yoshioka, the responses of readers started to grow. The number of subscribers among students, in particular, grew. This resulted in the introduction of student exhibitions in the magazine as well.”

___

To read the original text excerpt (in Japanese) from Architecture of the Shōwa Era, please visit Shinkenchiku.online.